|

| Images Courtesy of Radiance Films |

Forming something of an actor-director team with Franco Nero

who all but sheds away his larger-than-life screen persona to play an everyman

being pawned about by greater sociopolitical powers for their own mercurial

needs, Radiance Films and their aptly named Cosa Nostra boxed set

presents all three films in newly restored 2K digital restorations and a

plethora of extras including but not limited to a 120-page collectible booklet.

The resulting trilogy of films tonally and

thematically speaking are not that far removed from Vittorio Salerno’s own No,

the Case is Happily Resolved from Arrow’s Years of Lead Italian

crime thriller box, highlighting the miscarriages of justice purported by

mobsters in power from on high against unassuming everyday people. With this, let us take a closer look at

Radiance Film’s eclectic, handsomely restored collection of Italian mob dramas

starring the legendary Franco Nero in three of arguably his best, most

underrated roles.

The Day of the Owl (1968)

In rural Sicily around dusk, truck driver Salvatore

Colasberna is driving a truck of cement to a highway construction project when

he is besieged by an assassin who shoots him dead but not before being witnessed

and heard within an earshot of the home of Rosa Nicolosi (Claudia Cardinale)

and her husband. As police captain Bellodi

(Franco Nero) and crew start mounting their investigation, the captain uncovers

a labyrinthine system of criminal mafia factions that are more than a little

involved in the construction project and may know a thing or two about

Colasberna’s murder, pointing to Don Mariano Arena (Lee J. Cobb) as the primary

suspect in what could be a corruption racket.

Meanwhile Rosa herself falls under suspicion when her husband goes

missing while shirking off the reputation of being the ‘town tart’ while a

neutral informant named Parineddu (screen legend Serge Reggiani) finds mercurial

criminal forces closing in around him.

All the while, whatever actions the captain makes against Don Mariano

and his empire get pushed back to where he started.

Based on the 1961 novel of the same name by Leonardo

Sciascia after the success of Elio Petri’s adaptation of Sciascia’s novel To

Each His Own and adapted for the screen by Ugo Pirro and director Damiano

Damiani, The Day of the Owl (released in the US as Mafia) kicks

off the Cosa Nostra trilogy of crime films with an especially sardonic

and defeatist crime drama about the inseparability of mobsters with politics

and police. As we side up with Captain Bellodi

(an ever-powerful Franco Nero) and see one roadblock after another being put in

his way by gangsters hiding in plain sight who even make attempts on the

captain’s life to his face, one gets the sense we’re not watching to see him

solve these crimes but to see how easily they sweep their transgressions under

the rug hiding in plain sight.

Lensing the Sicilian countryside contrasted with the upscale

living of the Roman cityscape with handsome clarity by Pier Paolo Pasolini’s

longtime cinematographer Tonino Delli Colli and scored evocatively by L’avventura

and Hiroshima Mon Amour composer Giovanni Fusco, for all of its

murder and corruption depicted onscreen The Day of the Owl looks and

sounds lovely. The ensemble cast led by

Franco Nero including but not limited to legendary character actors Lee J. Cobb

and Serge Reggiani helps to boost the credibility of the production and

eventual The Leopard actress Claudia Cardinale radiates onscreen as a seemingly

single mom trying to protect her child while fending off leering and lecherous criminals

trying to take advantage of her.

Initially released in Italy circa 1968, the film was banned

by the Board of Censors who objected to the film’s profanity, acerbic attitude

towards the subject matter and uncompromisingly bleak finale. After a couple lines were changed however,

the ban was lifted and the film went on to become a box office hit in Italy and

helped spawn what would or would not become a recurring working relationship

between actor Nero and director Damiani.

A blistering critique of the cojoined dependency crime and crimefighting

have on each other, sometimes with the police force turning a blind eye to the mob’s

transgressions, The Day of the Owl helped pave the way for more

like-minded sociopolitical critiques of Italy at the time and help begin

ushering in Nero as a more serious minded actor taking on more artistically

challenging fare.

The Case is Closed, Forget It (1971)

Dandy upstanding architect Vanzi (Franco Nero) finds himself

behind bars over a petty traffic misdemeanor amid dangerous criminals and

mobsters whom he quickly learns are the real figures pulling the reigns of

power. As he settles into his

confinement, being shipped from cell to cell bumping into double-crossing

miscreants with their own self-serving schemes, he buddies up to a political

prisoner whom, it seems, both the mob and those tasked with upholding the rule

of law are out to get him. After a

prison-riot results in the death of one of its inmates possessing a note that

would’ve been an expose on the police corruption running through the police

system, Vanzi grows more involved in trying to intervene for the political

prisoner while putting his own safety and chances for parole on the line.

An intense, claustrophobic, sometimes suffocatingly

oppressive and choking prison Italian prison drama that’s as much about the

judicial system as it was about the rise of corruption in Italian politics and

law enforcement in general, The Case is Closed, Forget It is a hard-boiled

admission of defeat, a tough hitter that beats you down and kicks you a few

more times before you’re back on your feet.

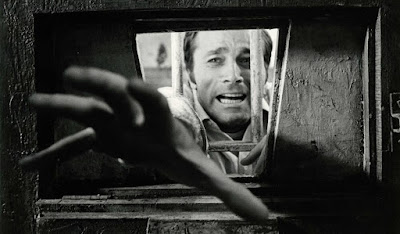

Much of this comes from seeing Franco Nero inside the squalid and

threateningly dirty prison sets and how his own demeanor starts to become

exhausted and strained over time.

Initially the clean-cut architect certain his freedom is around the

corner, as more and more misfortunes and threats to his life befall him we see

the wear and tear taking a toll on the once formally composed family man.

Co-written by Damiani, Massimo De Rita and Dino Maiuri, for

all of its rancid squalor The Case is Closed, Forget It is handsomely

shot by Password: Kill Agent Gordon cinematographer Claudio Ragona,

expertly capturing the enclosed interior netherworld of the prison and renowned

composer Ennio Morricone’s score for the piece is appropriately chilling and

foreboding, suggesting a bleak fate for the film’s hero. Co-starring alongside Nero is Riccardo

Cucciolla as the political prisoner and British character actor John Steiner

makes a memorable turn as a flatulent sociopath. The actor who really leaves an unshakable

impression is Ferruccio De Ceresa as the ruthless prison warden who will break

whichever laws he can think of in order to maintain his ironclad grip on the

prison morale.

Searing and leaving an imprint on all who encounter it, The

Case is Closed, Forget It functions both as an indictment of the

then-fascistic judicial system as well as an uncompromising character study of

a man who comes to realize privilege may have more to do with freedom than

actual culpability. Moreover, everyone

you think you know might all be subservient to a greater implacable power and

the only ability you have is to recognize its evildoings. A great companion piece to the aforementioned

No, the Case is Happily Resolved with which its title card bears a

strong resemblance, The Case is Closed, Forget It is one of the best

Italian prison dramas you’ve never heard of and surely one of Franco Nero’s

most surprising turns as an actor.

How to Kill a Judge (1974)

They say life imitates art, but if you’re a film director

like Giacomo Solaris (Franco Nero) whose namesake consists of directing crime

thrillers involving political corruption, what happens when one of your films

engenders copycat crime? That’s a

question Solaris is forced to grapple with upon the release of his latest

project, a hit movie about a judge who gets whacked after buddying up too

closely to the mob. A disdainful

Sicilian magistrate and his beleaguered wife demand the film be withdrawn from

circulation, but then the judge turns up dead like one of the victims in

Solaris’ film. As the widow pins blame

on the filmmaker, he starts to notice friends and colleagues in his circle

start dropping dead in increasingly nasty ways and soon realizes he’ll be next

if he doesn’t find out the truth behind the judge’s mysterious murder.

Opening on a mournful cue by Riz Ortolani that sounds very

like his own score for No, the Case is Happily Resolved as La Grande

Bouffe cinematographer Mario Vulpiani’s camera careens across the Roman

cityscape, How to Kill a Judge from the beginning implies a series of

injustices and double-crossings will ensue before being conveniently swept

under the rug. More of a sociopolitical

critique in the same vein as their prior prison drama The Case is Closed,

Forget It than a straightforward poliziotteschi, the film is also a

critique of the ways in which politics, the mob and the media go hand in hand

with one pawn manipulating the other into action. Over time it becomes less about who is

responsible for the judge’s death than how these two polar opposite extremes of

crime and criminal justice coexist if not co-depend on each other.

As with The Case is Closed, Forget It, the film’s hapless

director Solaris played by Franco Nero is a bit of a patsy whose film about the

takedown of a corrupt judge provides mercurial forces all the ammunition they

need for a ruthless coup d'état. French

actress Françoise Fabian as the film’s grief-stricken widow Antonia Traini

gives a ferocious performance with fierce angry eyes that could be hiding

something more sinister. Making a

memorable screen turn is character actor Renzo Palmer as director Solaris’

longtime friend and investigator who finds himself torn between maintaining

balance and doing what his heart says is right and true. And there’s the collective of mob assassins

who start picking off people in the director’s circle in steadily more vicious

ways while power players on opposite sides of the fence make ceremonial kisses

and handshakes.

While not as bleak as The Case is Closed, Forget It, Damiano

Damiani and Franco Nero’s follow up film is no less caustic and being about

life imitating art is kind of meta. Despite

its occasional bursts of extreme violence and the intensity of the

performances, How to Kill a Judge functions as a blistering critique of

how one man’s creation can be used to foster ulterior motives while calling

into question the personal responsibility a filmmaker has towards its subject

and the public in general.

A social commentary on the power of the movies involving

real world consequences and how often codependent systems of crime and corrupt

crimefighting will cover each other’s backs, How to Kill a Judge ultimately

proved to be the last film in the director’s loose trilogy about the Italian

mob as well as the concluding piece in Radiance Films’ Cosa Nostra boxed

set, rounding out the trio of films as a searing collection of neo-noir

influenced crime dramas aided by a gifted screen actor unafraid to take risks

and play conflicted, even troubled characters wading their way through a minefield

in broad daylight.

--Andrew Kotwicki