|

| Images courtesy of United Artists |

Emmy-award winning television director Ralph Nelson best

known at the time for directing both the 1956 Playhouse 90 teleplay and

the 1962 feature film version of Rod Serling’s boxing drama Requiem for a

Heavyweight maintained steady work in television until 1963 when he began

more extensive feature film directing. Drawing

from his economic television experience and working in as many as two pictures

per year between 1963 and 1970, the prolific microbudget filmmaker not needing heavy

means to make a picture worked quickly yet effectively as he swept numerous

film festival awards circuits with his extensive yet quickly rendered

oeuvre. Ultimately Nelson who also

served as a part-time character actor would generate two films in 1963: the

Jackie Gleason/Steve McQueen buddy comedy Soldier in the Rain and the Oscar

winning Sidney Poitier starring dramedy Lilies of the Field.

Based on William Edmund Barrett’s 1962 of the same name

which was partially based on the author’s own experiences with the Benedictine

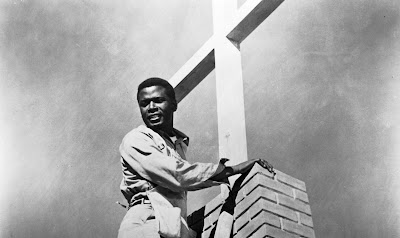

nuns of the Abbey of St. Walburga in Colorado, it tells the story of black handyman

Homer Smith (Sidney Poitier) who is drifting through an Arizona desert when he

makes a pit stop at an isolated farm looking for water for his car. There he meets a group of nuns who have

emigrated from former East Germany, spearheaded by the headstrong Mother Maria

Marthe (Austrian architect Lilia Skala in a semi-autobiographical role) who are

wanting to build a chapel for the Mexican American population nearby. Initially reticent to commit to the task as

Mother Maria refuses payment after quoting the Bible’s Sermon on the Mount,

Smith eventually meets with a local café manager named Juan (Stanley Adams) and

agrees to construct the chapel after learning of Mother Maria and the sisters’

escape from the Nazis. As he offers free

English lessons at the dinner table and tries to form camaraderie with the Mexican

populace, Smith finds himself clashing with Mother Maria’s stern worker-bee

outlook on life, threatening to jeopardize completion of the chapel.

Heartwarming, charming and straightforward, Lilies of the

Field is very much an actor’s film largely resting on the shoulders of

Sidney Poitier who imbues the character of Homer Smith with a larger-than-life

presence. Almost leaping off of the screen

spectacularly with energized and wholly confident delivery, it came well into

the actor’s filmography following Blackboard Jungle and The Defiant

Ones. While the dramatic conflict of

the story itself is somewhat lighthearted if not playfully whimsical, what is

hinted at regarding the German nuns’ wartime experiences lands heavily. Almost equaling Poitier’s prowess is Lilia Skala

as the determined and stern Mother Maria who shows no fear of backing down from

Poitier as he tries to lay down the law of how he should be compensated for his

time. Stanley Adams as the Mexican

bartender, having started out playing that role in Death of a Salesman

before moving onto Ralph Nelson’s adaptations of Requiem for a Heavyweight,

is a comforting presence and serves up comic relief opposite Poitier when they

start dueling over whether or not he’ll accept outside help building the

chapel.

Reportedly shot within fourteen days in Arizona largely on a

ranch owned by Linda Ronstadt’s family by multiple Academy Award nominated

cinematographer Ernest Haller with a very early score by Jerry Goldsmith, the

$247,000 quickie wound up becoming a critical and commercial favorite out of

the gate. Grossing around $7 million and

garnering five Oscar nominations including Best Picture, it ultimately won

Poitier the Best Actor award. Further

still, the film’s gospel hymn ‘Amen’ sung by Poitier’s character albeit dubbed

over later by Jester Hairston (who also wrote the song) became increasingly

popular in the years since the film’s release.

Though Poitier would express reservations about the role before and

after the film’s Oscar win, it nevertheless canonized the actor as a true

American original in a film that plays beautifully to his strengths and in a

way started paving room for what would or wouldn’t develop years later into the

New Hollywood movement.

--Andrew Kotwicki